Why Agentic Programming Feels Hollow, And Why I Stopped Caring

Introduction

I’ve been wanting to write here again for a while, but just couldn’t find a topic I wanted to talk about enough that didn’t feel like it was either:

- Reactionary “Can we stop whining about this shit now?” cynicism,

- Saying something that didn’t need to be said because other people already had.

So, rather than trying to kick that off with something polished or ambitious, I figured I’d just say where I’m at right now. Work has been stressful. Really stressful, if I’m being 100% with you.

It’s that kind of sustained, background stress that slowly drains your energy if you’re not paying attention. The kind that makes even things you like start to feel heavy if you’re not careful. That’s been shaping how I build lately more than I realized.

I adored digging into the absolute weeds when I was doing the C roadmap — but I’d clearly burned out on being that deep in the grass for a while.

Plus, I had some little projects I wanted to try out, and I’d be lying if I said the march of AI coding and the army of people who won’t shut the fuck up about it didn’t have a part to play, too.

I figured doing something was better than doing nothing, and I’d always wanted to start playing around with OpenAI’s agentic coding assistant, Codex. My Bishop Fox colleague was an early AI adopter and has recommended it for projects for a while, so I spent the last couple of weekends playing around with it.

Figured I should at least “know my enemy”, if this is the thing that’s going to drive me out of work (checks notes)…2 years ago?

Next year? Tommorow?

Honestly, I lose track of when I’m meant to become unemployable, these days.

So, I’ve been using it to build a set of CLI-launched helper tools that I’ve wanted for a while, in tech stacks I have no intention of diving deep into.

The feelings have been…interesting, to say the least.

chmod +x ./senseofownership.sh

My first impressions of Codex are good, after I managed to assuage my fear that I wasn’t going to receive a $9k API bill from using it.

Legitimately, it’s impressive what Codex can do in terms of turning natural language input into actual usable code. There are a few caveats to that judgement, though - which I’ll go through as I tour the three projects I’ve used Codex to build recently.

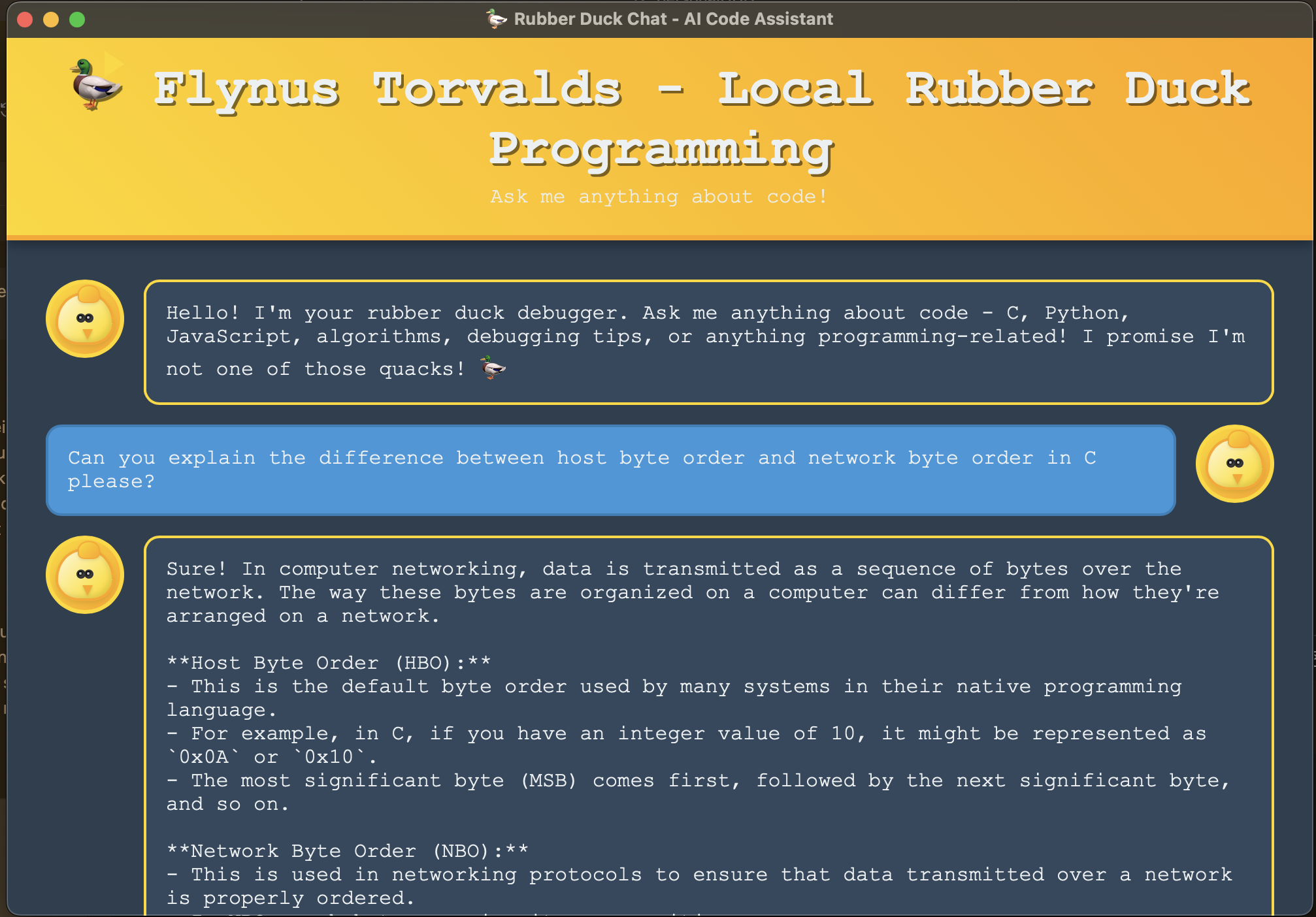

Flynus Torvalds: The Actual Rubberduck Syntax Helper

The first project I utilized agentic programming for was something I’ve wanted to have for a while - an AI-powered “rubberduck” coding assistant.

I’ve always felt a weird bit of “craftsman’s guilt” utilizing AI code or heavily working from it, but I fundamentally don’t see asking ChatGPT for language syntax help or checking Linux commands as any different from what we used StackOverflow for back in the day.

I’ve really enjoyed utilizing Ollama since I first tried it building Dashi the chess app, and wanted to use it again here. I also really wanted to make something that was entirely local with no API integrations, so I could never get priced out of using it.

You know, for when the entire financial model of consumer AI collapses and it costs a billion dollars a month to use Claude Code.

This is where I came upon my first real observation about agentic programming tools like Codex:

These tools genuinely cannot creatively “think” the way AI boosters want you to believe. They are AWFUL when you don’t have a strong idea of what you want the outcome of your project to be. They need tight scope and a strong impression from you on what “good” looks like.

Once you do have that scope tightened up though? Hoo boy, are you off to the races!

I had a fairly locked down idea of what I wanted this project to be:

- Entirely locally stored and run on my Macbook (and thus MacOS),

- Single user (no auth needed)

- Rapid load time and little to no latency

- LLM/natural-language input

- NO WRITING CODE FOR ME, just answer coding syntax and conceptual questions.

Once I’d arrived at this general set of functional requirements, building a detailed prompt to Codex was the next step.

Based on what I mentioned as requirements, it suggested the following:

- Python FastAPI backend plus pydantic and some other libraries,

- Ollama (I already had it) and a small Qwen-1.5b model that is good at short coding questions, but won’t crush my 2021 M1 Macbook Pro.

- Tauri, a framework for MacOS apps I’d never heard of, but apparently works well for the purpose.

It’s a little slower, but I wanted to review each change as it happened to ensure I knew what was happening. And honestly, Codex did a great job of explaining why it makes a given change, if you ask in the following part of the chat.

It genuinely took about 40 minutes from front to back to arrive at something that I legitimately use all the time and wanted to exist, with some minor UI tweaks taking most of that.

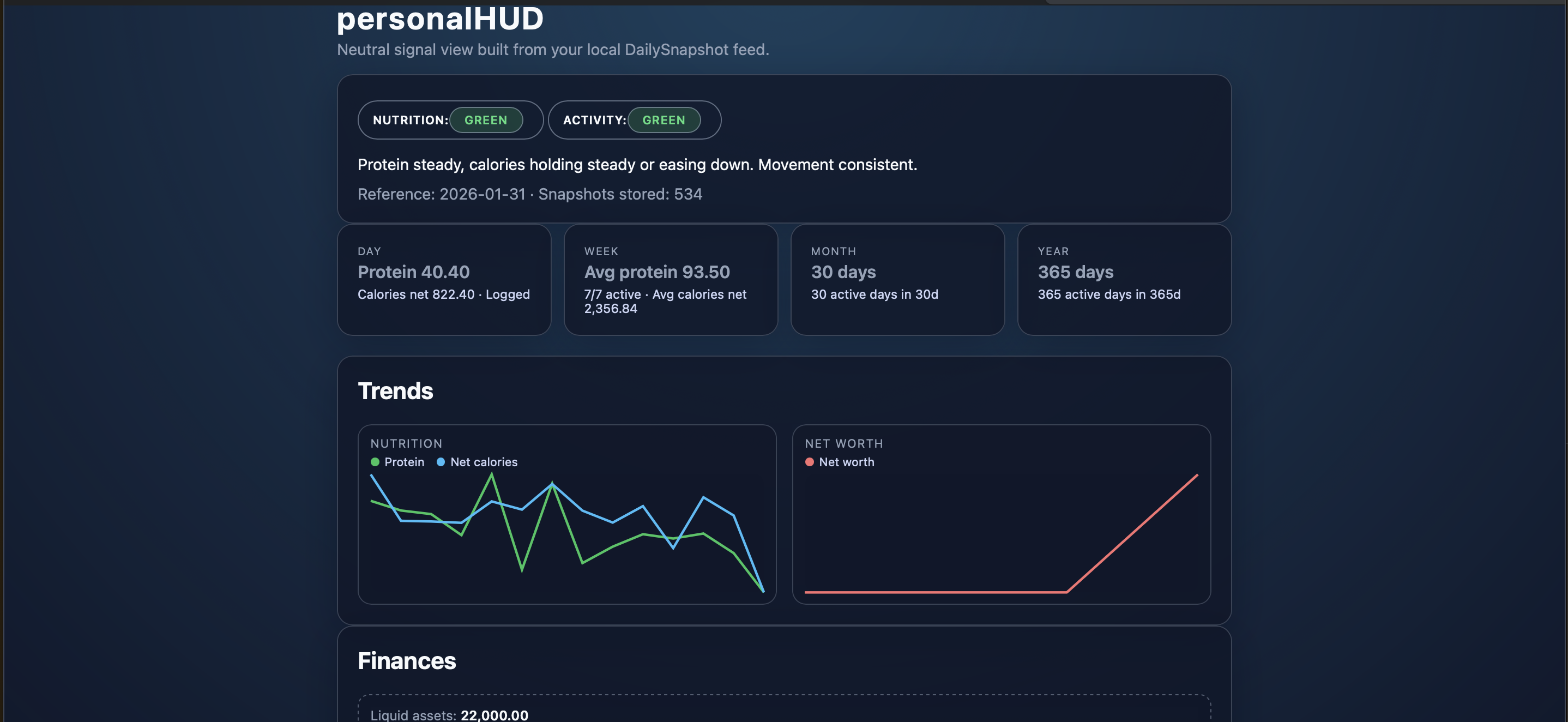

Personal HUD: Integrating Outside Data

This next one was something I’d been noodling on for a while, mostly after having to pay my annual renewals for two apps I use daily:

- MyFitnessPal (for food logging)

- Strava (for exercise logging)

I also wanted somewhere I could just pull up a quick view of “where I’m at” in terms of nutrition, exercise and general financial situation.

BUT, I also didn’t want to spend months trying to troubleshoot a custom API integration for two different platforms, plus working out how to safely get my financial information into there.

In an Ouroboros-esque move, I actually utilized ChatGPT 5.2 to give me an extremely detailed Codex prompt for this, a truncated version is below:

You are implementing a MyFitnessPal CSV ingestion module for a single-user, local-first personal HUD.

Constraints

No authentication

No multi-user logic

No external APIs

No mutation of historical data

Append-only storage

Deterministic behavior

Input Files

The user provides exactly three CSV files exported from MyFitnessPal:

Nutrition-Summary-*.csv

Exercise-Summary-*.csv

Measurement-Summary-*.csv

Canonical Output Model

Normalize all data into daily snapshots of the following shape:

type DailySnapshot = {

date: string; // YYYY-MM-DD

nutrition: {

protein?: number;

caloriesGross?: number;

caloriesNet?: number;

hydration?: boolean;

fiber?: number;

logged: boolean;

};

exercise: {

active: boolean;

workouts?: number;

};

After ingestion:

The system must be able to query snapshots by date

Partial days are valid

Missing data must not be treated as failure

Philosophy

This ingestion pipeline exists to support trend and direction, not precision.

Simplicity and determinism are more important than accuracy.Codex did a great job with this one, because ChatGPT’s web interface works great with structured information and standardized output. Because that’s what it got trained on when it hoovered up everything anyone ever wrote and uploaded.

The fact that this is entirely CLI-launched meant no local app, either. Just a quick launch of a React page for a UI in the browser at localhost to see some rough data!

Which again, was all I ever needed. Tight scopes make for great Codex projects.

It’s a shitty UI/UX designer though, and will often break more than it fixes in that regard.

I will say though, this took a lot longer than the rubber duck app and I think that mostly came down to the UI/UX troubleshooting, which brings me to my second observation on agentic programing:

Use stuff like Codex and Claude Code for “glue” and “plumbing” code, do the UI parts yourself. Play to the tool’s strengths instead of forcing your way through something not suited for the purpose. Your output will be better for it.

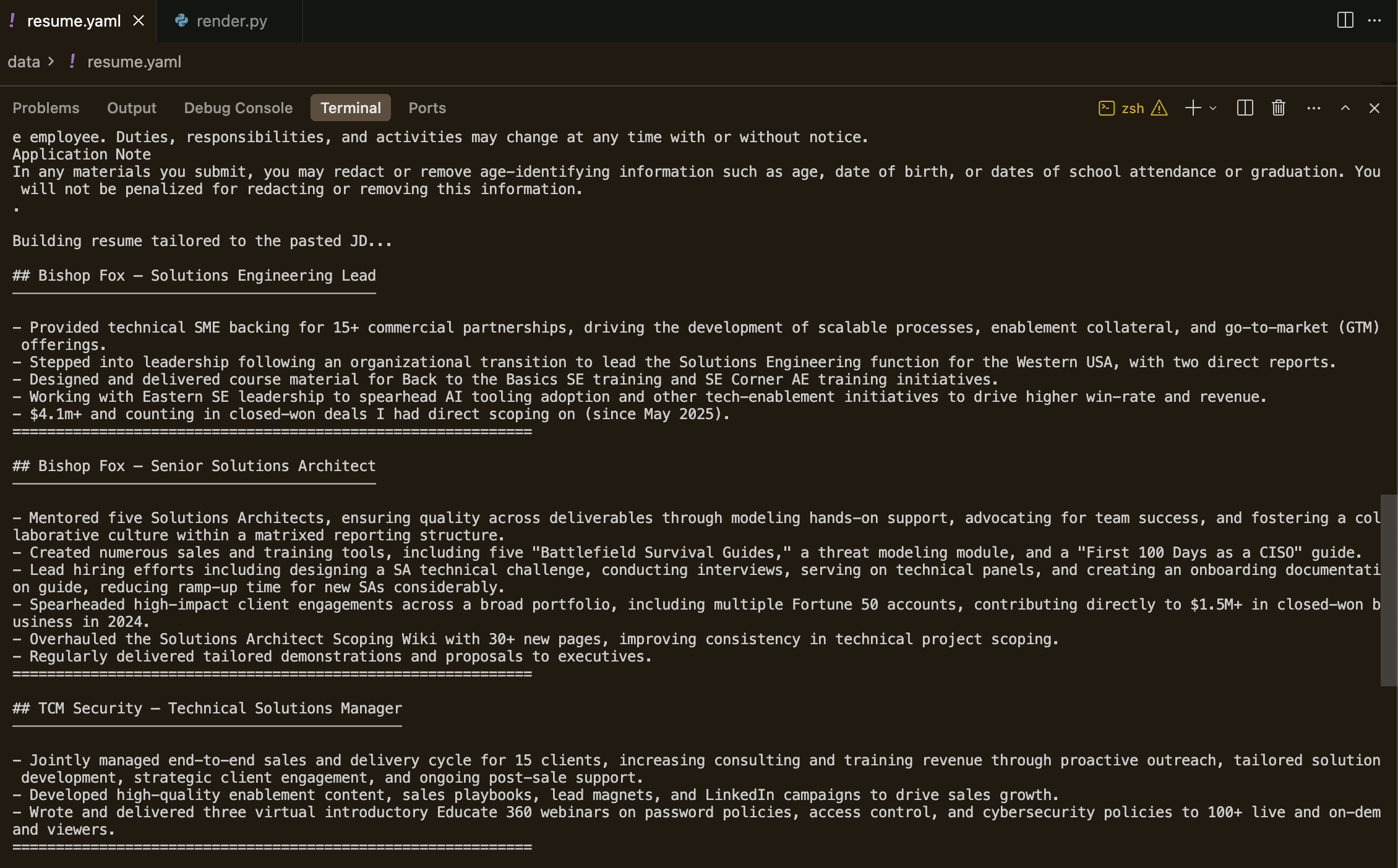

Resume Engine: By Far My Favorite

This one, Codex knocked out of the absolute ballpark.

The prompt looked a little something like this, after some massaging from ChatGPT’s web client. It worked great last time, so figured I’d do it again here:

You are acting as a deterministic code generator.

Context:

- I have a YAML file open containing a role with claims.

- Each claim has fields like id, text, tags, metrics.

Task:

- Write a simple Python script named render_bishop_fox.py.

- The script should:

1. Load data/bishop_fox.yaml.

2. Extract the first role.

3. Print a Markdown section with:

- A header containing company and title.

- A bullet list of each claim.text value.

- Do not invent, summarize, or reorder content.

- Keep the code simple: no classes, no frameworks.

Output:

- Provide only the Python code.Because the functional requirements were so simple, Codex ate this up.

- Decompose my resume into one YAML file, with each bullet becoming a claim with tags etc.

- Write a Python script that prints out customizable chunks of that YAML file for different roles, for different topics etc.

- No frameworks, no classes, no generative content.

As you can see, within about 30 minutes, I was able to get something usable up and running, in a format that I can basically just update ad infinitum with new claims.

Speaking of adding new claims, Codex is great at adding additional features if you’re able to strictly define what you want the outcome to be. The more detail the better.

I asked for a feature where I can add a —jd-text flag to the tool render.py Codex built, through the following prompt:

I wonder if we can use the flag --jd-text to then start a wizard of sorts, kinda like when you SSH into a host for the first time, so you can copy in the JD text from a web page, like we did in the chat here (as a test).Codex took the ball and ran with it, adding this —jd-text feature functionally in seconds.

I asked for a feature to make sure I can add extra claims (resume bullets) as I gain experience and do projects, without adjusting the YAML file and ensure data normalization, so render.py doesn’t break. This was the prompt:

What would be the best method long-term for adding extra content to the YAML file? I wondered if a simple web form could work? Actually, I think a cli-based helper would be the move - means we do not have to worry about APIs and handoffs etc. I mostly just wanted to make sure that whatever I typed in got normalized properly to add to the data set.Codex one-shotted this very specific ask, doubly proving my point that this tool works way better when you know exactly what you want and what the desired outcome. It’s a plumber, not a designer.

However, to give credit where credit is due: I use this tool all the time.

Codex built something legitimately useful for me, in a timescale I couldn’t have hit in my wildest dreams.

This brought up a lot of weird feelings, which I’ll go into next as I tie this article up.

Sometimes It’s The Vending Machine, Sometimes It’s The Beef Wellington

The Codex projects all work, let me clear. They were fast to build.

But when I was done… I felt…basically nothing. For a bit, that bothered me.

I thought maybe I was doing something wrong, or missing out on the “real” experience of building. But I think what was actually happening is simpler.

I was using AI-assisted projects to keep moving without risking something I cared about more.

The truth is, I’d been avoiding my more craft-heavy projects — game experiments, low-level C/C++ work, math notebooks, a narrative card game I’ve been tinkering with.

Not because I didn’t value them, but because I didn’t want them to start feeling like work. I didn’t want stress, expectations, or productivity pressure leaking into the things I use to recharge.

So I kept them at arm’s length for a while. And I’ve learned that this is actually completely okay. Right now, I’m mentally splitting my projects into two buckets:

- There are utility projects, where the goal is speed and outcome. These are allowed to be AI-assisted, boring, and unromantic. They exist to make my life easier, nothing else.

- Then, there are craft projects, where the point IS the process. These are allowed to be slow, inefficient, and stubbornly manual. They exist almost entirely because I ENJOY wrestling with them.

Once I stopped expecting utility to feel meaningful — and stopped expecting craft to be efficient — a lot of that guilt disappeared.

Sometimes you grab something from a vending machine because you’re hungry and tired and you just need fuel.

Other times you spend an entire evening cooking something unnecessary and imperfect like a Beef Wellington, because you want to point at something and go “LOOK I MADE THIS!”.

Both are valid. Confusing them is what causes friction.

So that’s where I’m at.

I’m building what I need to build, protecting what I care about, and giving myself permission to let those be different things for a while.

I think I’m going to head back to the low-level mines for a long while next though, but with a new-found perspective and far less self-flagellation, self-imposed rigidity, or the need to justify why I build the way I do.

Alright, peace!

Matt/jawndeere